Room Summary

The engagement began by exploiting a flaw in the Joomla! CMS that exposed its configuration file, allowing us to recover a set of credentials. We then used those credentials over SSH to gain shell access to a container.

From within that container, we performed network enumeration and identified another web application vulnerable to insecure deserialization. Exploiting this weakness provided us with shell access to a second container.

Finally, since the container was granted the SYS_MODULE capability, we leveraged it by loading a kernel module. This escalation enabled us to break out to the host system, where we obtained a shell and successfully completed the room.

Initial Enumeration

Nmap Scan

We start with a port scan:

There are three open ports:

- 22 (SSH)

- 80 (HTTP)

- 2222 (SSH)

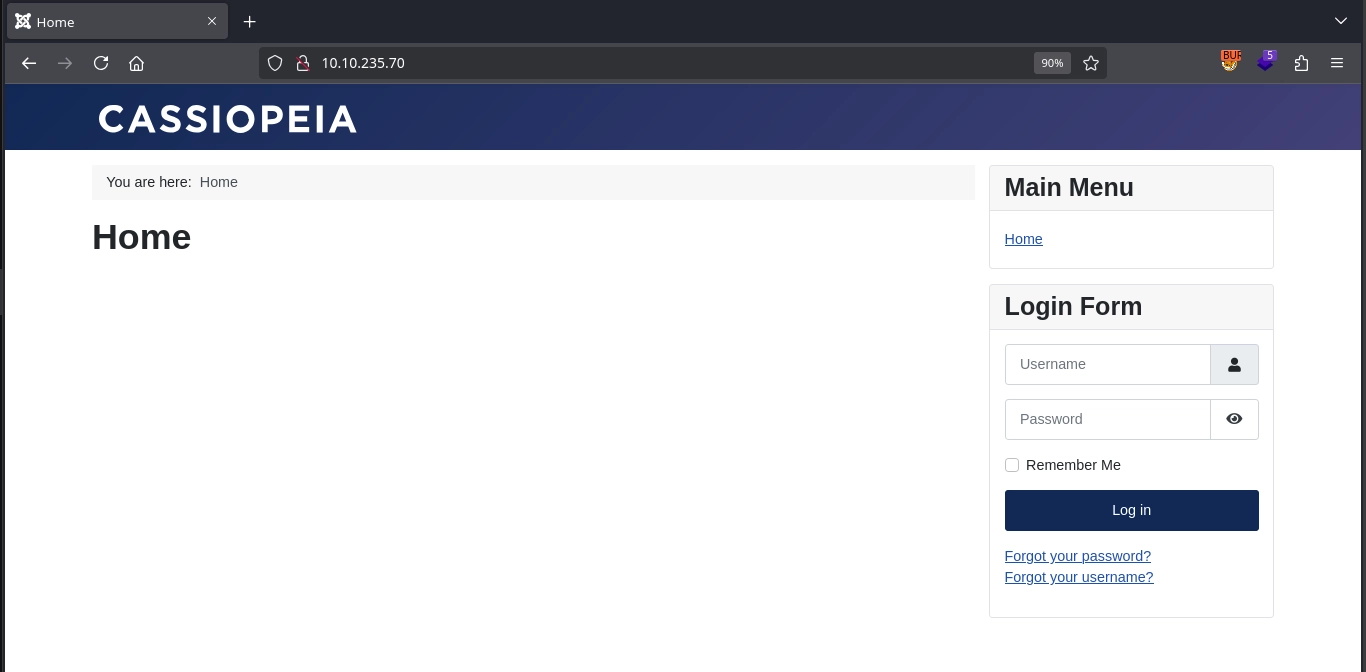

Visiting http://10.10.235.70/, we see a simple page with a login form.

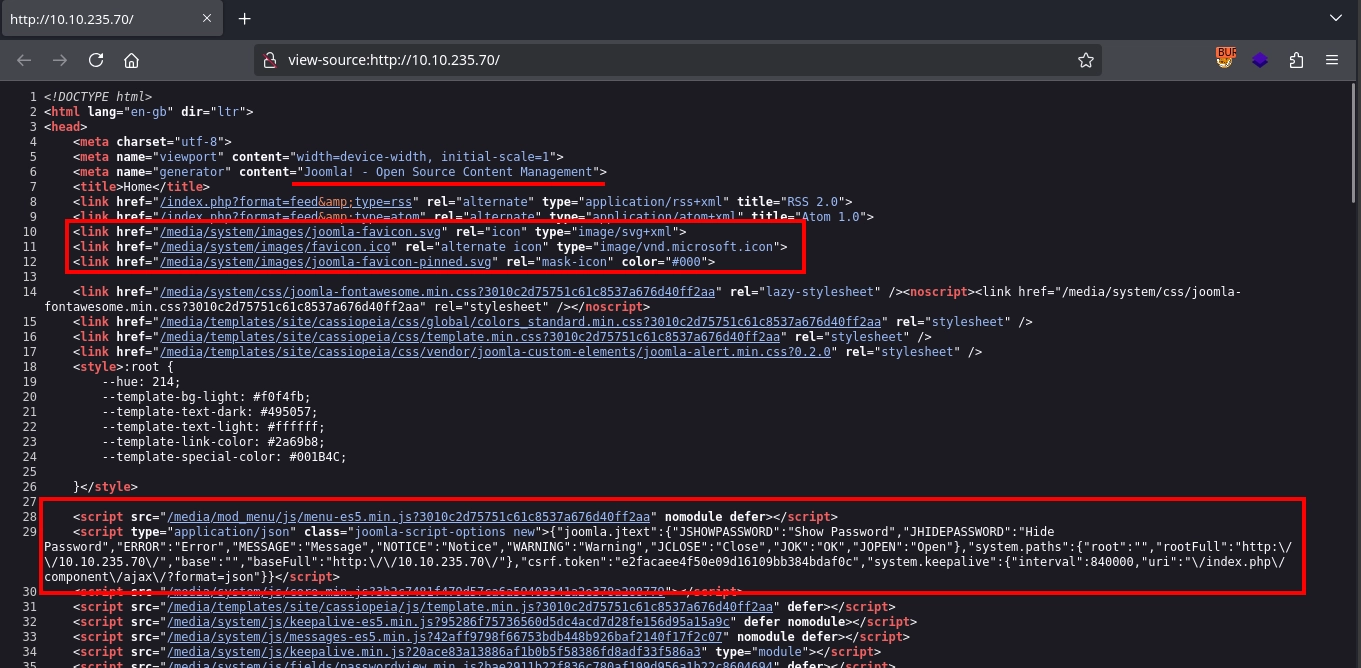

Checking the source code for the page, we see that it uses Joomla! CMS.

Since it uses Joomla!, by making a request to the /administrator/manifests/files/joomla.xml endpoint, we can discover the version as 4.2.7.

Exploitation

CVE-2023-23752

While testing Joomla! v4.2.7 we identified CVE-2023-23752. By adding the query parameter ?public=true to certain API endpoints we can bypass access controls. Requesting /api/index.php/v1/config/application?public=true returns the Joomla! configuration, which contains the database credentials.

We don’t have access to the database as it is running on localhost; however, we can still try these credentials against the two SSH servers.

Trying them against the SSH server on port 22, we see that we are not able to authenticate with a password.

However, trying them against the SSH server on port 2222, we see that password authentication is enabled and the credentials also work, giving us a shell as the root user inside a container.

Obtain User Flag

Enumerating Internal Network

Inside the container, we don’t find anything useful. But checking the network configuration, we can see that it has the IP address 192.168.100.10 and is in the 192.168.100.0/24 network.

Nmap is already available for us inside the container, so we can use it to scan the network for other hosts. Doing so, we can discover that apart from us and the host machine at 192.168.100.1, there is another container running at 192.168.100.12.

Once again using nmap to scan this container for open ports, we can discover port 5000 is open.

Checking 192.168.100.12:5000, we can see it is a webserver.

Insecure Deserialization

We can use SSH to forward the port to access the web server directly, either by spawning the SSH command line with ~C on our active session and running -L 5000:192.168.100.12:5000. Note: You might need to set EnableEscapeCommandline=true in your SSH configuration to enable the command line.

Or simply adding the -L 5000:192.168.100.12:5000 argument to our initial SSH command:

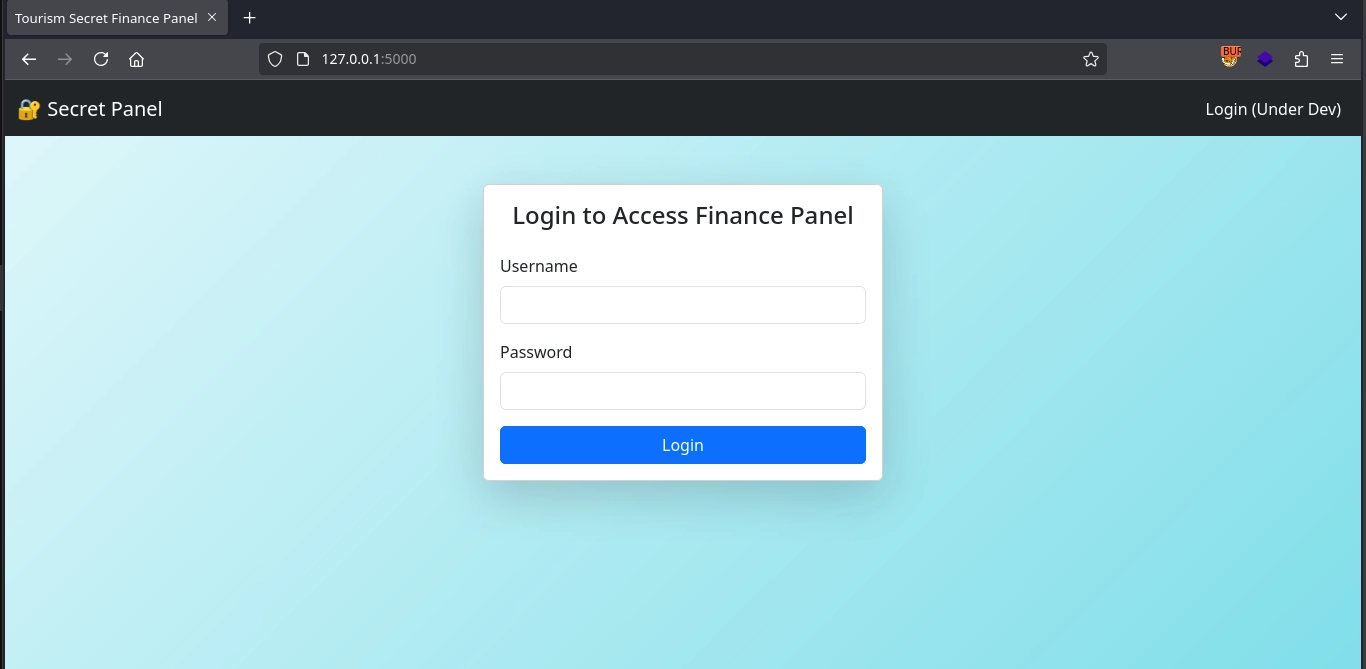

Either way, visiting http://127.0.0.1:5000/ now gives us access to the web application at 192.168.100.12:5000, where we see a login form.

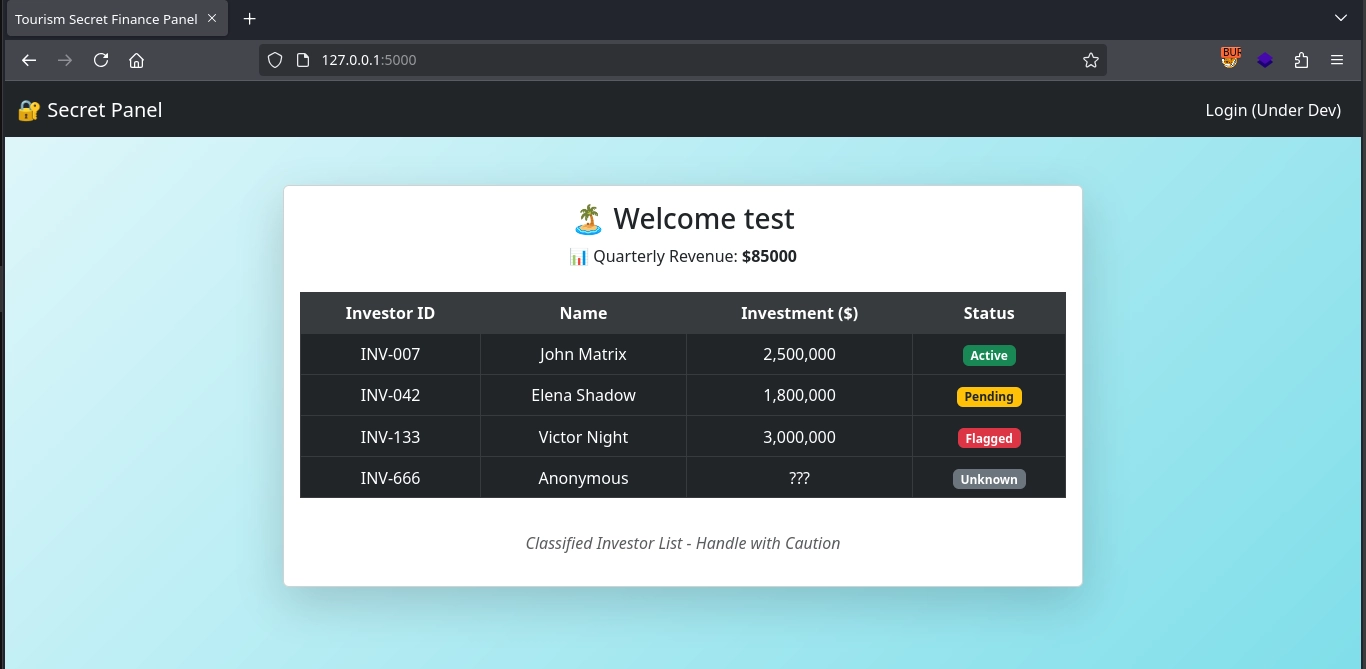

Trying to log in with any credentials works, and we simply get a list of investments.

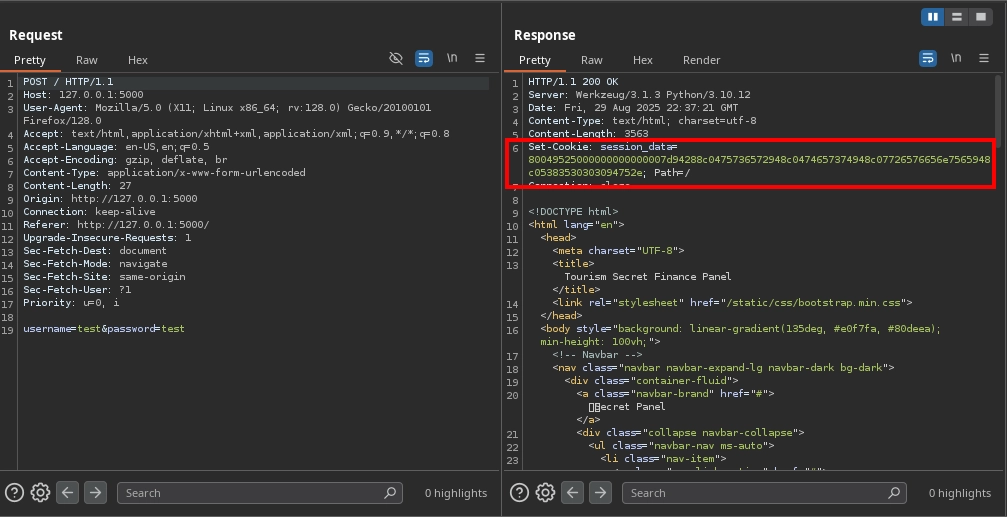

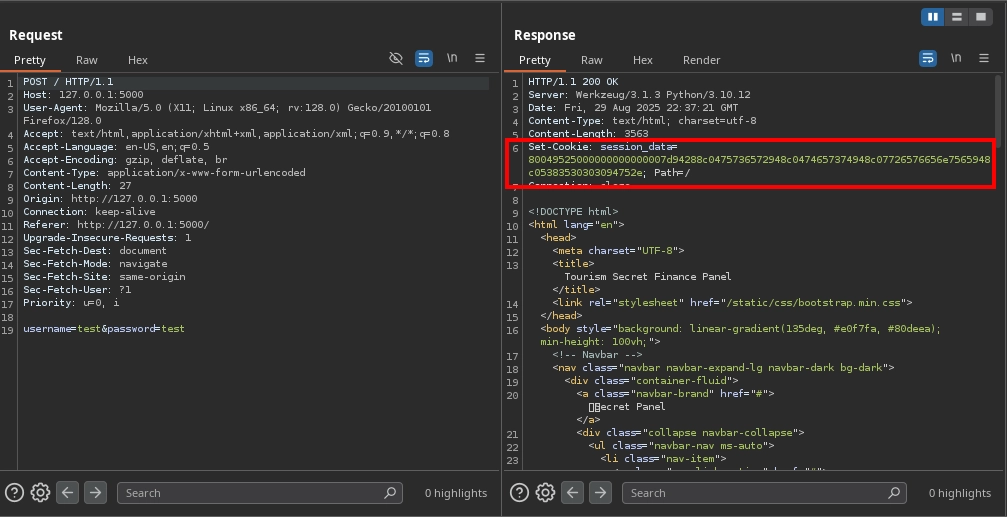

We don’t see much on the website itself, but checking our login request in Burp Suite, we can see the server setting an interesting cookie called session_data.

Looking at the cookie value, we can quickly identify it as a Python pickle serialized object in hex as it starts with 8004 (pickle protocol version 4) and ends with a dot (2e). We can confirm this using pickletools:

Or simply by deserializing (unpickling) it ourselves:

If in our subsequent requests the session_data cookie we have sent is not sanitized and used simply by deserializing it, we can use this to achieve RCE by creating a serialized object with a malicious __reduce__ method that runs a reverse shell payload which gets executed when the object is being deserialized as such:

Now running the script to create our malicious pickled object payload:

Sending our payload in the session_data cookie by making a request to the server, we can see the server hanging.

And on our listener, we get a shell as root in another container and can read the user flag at /root/user.txt:

Root Flag

Container Escape

Once again, we don’t find anything useful inside the container; however, checking our capabilities, we can notice that we have the cap_sys_module capability set.

The cap_sys_module capability allows us to load kernel modules and since the container shares the kernel with the host, we can use this to execute code on the host. First, we create a basic kernel module that runs a reverse shell payload upon initialization:

We also create a Makefile to compile it on the target:

Now we can use make to compile our module as shell.ko

First, starting our listener:

Now installing our module using insmod:

Going back to our listener, we can see a shell as root on the host and read the root flag at /root/root.txt to complete the room.